Leeds & Catlin Records: A History of Leeds & Catlin

By Allan Sutton

For nearly a decade, the Leeds & Catlin Company flaunted phonograph-related patents, presenting a serious challenge to legitimate operators in the nascent recording industry. Edward F. Leeds entered the record business legitimately enough, forming a partnership with Cleveland Walcutt and Walter Miller after they purchased the North American Phonograph Company’s recording and duplicating facilities in September 1894. Following Miller’s departure, the company was reorganized as Walcutt & Leeds. Loring L. Leeds had joined the firm by November 1896, when he was sued by the American Graphophone Company (Columbia) for infringement of their Bell-Tainter patent — the first in a long line of legal actions against the Leeds’ companies.1 A month later, the company slashed retail prices on its cylinders to 50¢ each, half of what Columbia was charging.2

Walcutt & Leeds supplied a substantial number of master cylinder recordings to the newly formed National Phonograph Company (Edison) during 1897.3 However, National Phonograph quickly proved capable of handling its own recording operations, and the connection was severed in early 1898. Walcutt & Leeds carried on, marketing cylinders under their own brand that continued to under-cut Columbia’s and Edison’s retail prices by half.

In early 1898, Judge Wheeler (United States Circuit Court of the Southern District of New York) found Cleveland Walcutt and Edward Leeds guilty of contempt for ignoring an injunction in an 1897 suit filed by the American Graphophone Company (Columbia). The firm of Walcutt & Leeds had been dissolved shortly after the 1897 ruling but was subsequently reorganized as The Walcutt & Leeds Company, Ltd. Having been assessed only minor damages and costs,4 Walcutt and Leeds were soon back in production. However, the legal skirmishing with Columbia continued, involving both Edward and Loring Leeds in separate cases, and in 1899 Walcutt & Leeds was finally forced to accept a consent decree following yet another adverse ruling.5

In June of that year, Edward Leeds dismantled the embattled firm, and the remaining Walcutt & Leeds inventory was sold off by the Excelsior & Musical Phonograph Company.6 In partnership with L. Reade Catlin, he reorganized as the Leeds & Catlin Company, which according to its incorporation filing would manufacture and sell phonographs. Loring Leeds’ name was conspicuously absent from the list of directors, as was any mention of manufacturing records.7 Among the company’s earliest investors was Ira D. Sankey, who recorded many of his gospel hymns for Leeds at the turn of the century.8

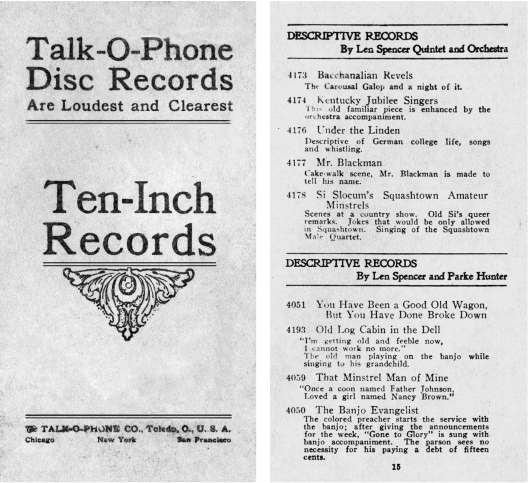

The new company resumed cylinder production in its studio at 53 East 11th Street, New York, where it would remain until the end. Veteran phonograph singer Dan W Quinn recalled it was “rather a small plant, but they did a land-office business for a long while.”9 However, Edward Leeds soon turned his attention to the newly emerging disc market. He found an ally in the Toledo-based Ohio Talking Machine Company, which began manufacturing phonographs in 1902. The Music Trade Review reported, “There is good Toledo capital back of the enterprise, the personnel of which will not be made known for the present, as business reasons render it advisable not to make known all of the details.”10 Ohio Talking Machine’s incorporators apparently served as little more than front-men. None had any known experience with the phonograph or recording businesses, and their names soon vanished from news reports. In time it was revealed that the company’s financial backers were Winant Van Zant Pearce Bradley and Albert L. Irish. Bradley allegedly had been involved in some early disc piracy,11 while Irish, a Toledo financier, had no experience in the phonograph or recording industries. The company was soon manufacturing and marketing phonographs under the Talk-O-Phone brand.1

For the first year of Leeds’ disc production, the records were marketed by the Talk-O-Phone Company (Toledo, Ohio), whose name appeared on the foil labels.By 1903, when it published its last known brown-wax cylinder catalog, Leeds & Catlin was preparing to manufacture discs. They would be marketed through Ohio Talking Machine, which apparently was having little success with its own Monogram disc records.13 Ignoring the crucial Berliner and Jones patents held by Victor and Columbia, Leeds readied its 7" foil-label discs for sale in late 1903. But the company had no sooner produced its first stampers, imprinted with the Ohio Talking Machine Company’s name, than Irish and Bradley reorganized as the Talk-O-Phone Company.14

Seven-inch Leeds records apparently reached the market in time for the 1903 Christmas shopping season, with labels crediting the defunct Ohio Talking Machine Company.15 The stampers were soon reworked to reflect the new Talk-O-Phone Company connection. Leeds’ 7" series seems to have been very short-lived; so much so that we have been unable to locate a catalog or even a significant number of pressings. The records were visually distinctive. Instead of a plain paper label, they bore imitation-gold foil labels pressed into a florid, deeply sculpted bas-relief, with the title and artist information in sharply raised lettering.

By early 1904, Leeds was producing 10" discs that retailed for 75¢ each — 25¢ less than comparable material on Victor and Columbia — or $9 per dozen. The early pressings were crude even by the lax standards of the day, often marred by irregular playing surfaces and dull shellac that was sometimes contaminated with bits of foreign matter. Early pressings had a thick outer rim with a deeply sunken playing area, resulting in a very thin pressing that was easily cracked. The pressing quality eventually improved, however, and the records were reasonably well recorded from the start. They offered popular material by many of the same studio performers that Victor and Columbia employed, at a more affordable price. The Talk-O-Phone Company imprint was removed after that company introduced its own line of 9½" discs in December 1904.16 Having severed its relationship with Leeds, Talk-O-Phone remaindered its inventory of about one-million Leeds foil-label discs for 50¢ each.17

The opening salvo in what would be a protracted legal assault on Leeds & Catlin came in the spring of 1904, just a few months after the first Leeds discs appeared. The American Graphophone Company (Columbia) accused the company of infringing its Jones patent #688,739, which covered lateral-cut disc recording in wax and a method for electroplating the resulting master. Hearings began in U.S. District Court in New York on May 16, 1904,18 and continued into mid-summer. Louis Hicks — who would represent Leeds & Catlin in this and the many cases that followed — filed a demurrer in which he argued, among other things, that the Jones patent was void for lack of invention, an assertion that Judge Platt dismissed as “obviously futile.” Platt rejected the demurrer and gave Leeds & Catlin ten days to respond, a deadline the company let pass.19

Leeds & Catlin was summoned back to court more than a year later, on August 14, 1905.20 By then, Hicks had changed his strategy, claiming that Columbia had no formal title to the Jones patent and therefore had no legal capacity to sue. To their dismay, the Columbia attorneys were indeed unable to produce the original patent assignment, as required by law. Judge Hazel refused to allow a certified copy to be entered as evidence, and Columbia’s plea was dismissed.

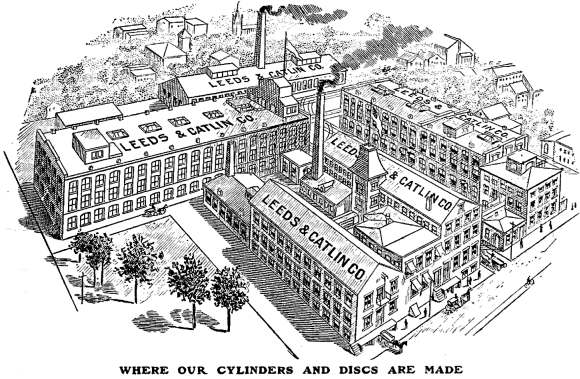

Columbia’s highly publicized loss came just as Leeds & Catlin was undertaking a major expansion. In September 1905, Leeds took over the former Worcester Cycle Company factory in Middletown, Connecticut, for its new pressing plant.21 Three months later the company announced it had installed fifty additional presses to accommodate the ever-increasing demand for its records. By the end of 1905, the plant was said to have an annual capacity of 150 million discs, which reportedly could be doubled without the need for additional equipment using an unspecified process patented by Edward Leeds.22

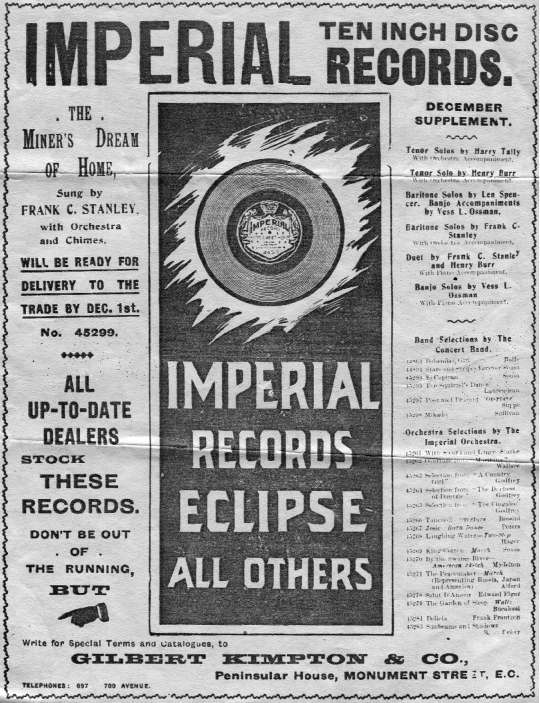

The Middletown plant acquisition coincided with the phasing-out of foil-label Leeds discs. The company had been offering two lines of conventional paper-labeled discs (the $1 Imperial and somewhat less expensive Concert) since mid-1905.23 In December 1905, Leeds sparked a price war when it reduced Imperial prices to 60¢.24 The price cut coincided with the end of production of Leeds’ foil-label discs production, the last of which were released in early 1906. The foil-label discs were soon being remaindered by various jobbers, including the Clinton-Close Company (Toledo, Ohio), which in February 1906 advertised its stock of 50,000 Leeds discs for 12½¢ each.25

Following discontinuation of the foil-labeled discs, Imperial was repositioned as Leeds’ flagship brand. Curiously, the Imperial labels never credited Leeds & Catlin (nor did any subsequent Leeds products), although no secret was made of the connection, at least among members of the trade. In a 1907 notice to its dealers, bristling with accusations and questionable legal claims, Leeds & Catlin declared, “The Imperial is a product of our factory, and we are proud of it.”26

Loring Leeds promoted Imperial records aggressively, demonstrating them on extended coast-to-coast tours and even venturing into Mexico on sales calls. In October 1906 The Talking Machine World reported that he was selling Imperial records “by the carload” in Salt Lake City. Among Leeds’ sales gimmicks was a list of purportedly extra-loud records made by a special process for “outdoor use.” Auditioned samples are not markedly louder than Leeds’ usual output.

December 1905 brought an announcement that Leeds cylinder production would “follow shortly” and would be “rich in grand opera masters.” Rumors to that effect had been swirling for some time. In early 1905, an apparent prototype label for a new Leeds cylinder box had come to the attention of Edison management.27 The label (a copy of which survives at the Edison National Historic Site) claimed the records were manufactured for the old New York Phonograph Company under authority of the North American Phonograph Company, which had once controlled Thomas Edison’s phonograph patents. It was an absurdly twisted claim, but it raised sufficient concern among Edison executives that Frank Dyer dispatched an attorney to Leeds & Catlin’s offices to investigate. There, it was learned that the company had not yet resumed cylinder production, but was planning to do so.28

Still, reports of Leeds’ re-entry into the cylinder business continued to appear regularly, although no records were forthcoming. In January 1906, the company claimed that its new cylinder records would be on the market by February 1.29 In the same month, TMW reported that Leeds could now manufacture celluloid cylinders for special orders of “sufficient size,” although “no firm carries it in stock, so far as can be ascertained, as the results by its use are said to have been not wholly satisfactory.”30 In March, TMW reported, “The Lambert [i.e., celluloid] records are not made by the Lambert people at the present time, but we understand that records similar to them are made by Leeds & Catlin, of New York.”31 However, beginning in March 1906,32 the launch date was regularly pushed back. In May 1906, the company admitted that its cylinder factory had yet to be become operational, although completion was said to be expected “inside of a month.”33 In the end, Leeds would not re-enter the cylinder market until early 1907, under the short-lived Radium brand.

In February 1906, The Talking Machine World reported that Leeds had received an order for one-million Imperial discs for export.34 The customer was unnamed but in all probability was Cooks, Ltd. (London), which began advertising Concert and Imperial records in April of that year.35 It was an exclusive arrangement, but in December of that year Cooks’ made the London firm of Gilbert Kimpton & Company sole British controllers for the Imperial line,36 under the direction of junior partner W. H. Glendinning.

Glendinning lost no time in inserting himself into Leeds & Catlin’s affairs, announcing in January 1907 that he had arranged for Leeds to record several British artists in New York.37 The first to be dispatched (and last, as it would turn out), at Leeds’ considerable expense, were Ian Colquhoun and Tom Child. They were accompanied on their voyage by Glendinning, who it was said would “make arrangements whereby the sales of these records will be materially increased throughout Great Britain.”38 Although Glendinning pronounced himself “very much pleased” with the resulting records, American buyers (and ultimately, Leeds’ management) did not share his enthusiasm, as TMW later reported:

The records, on being placed upon the American market, although principally for British consumption, proved “frosts.” … The net results of the visit is that the company bearing the expense of the importation [of the singers] are greatly disappointed with the demand for what they were led to believe were destined to be great sellers. As a matter of fact, outside of the famous operatic singers, it seems a waste of money to bring in, duty free, a bunch of popular singers, who may or may not have a reputation in “dear old Lunnon,” to swell the catalog of strictly American record manufacturers. At least, this is what the company in point asserted, and in reciting the facts, they added, “and we were stung good and hard.”39

Glendinning’s further attempts to sign performers for Leeds (reportedly including several British opera singers) seem to have been brushed off, and his plan to open an Imperial studio and pressing plant in England, under Edward Leeds’ supervision,40 never materialized. Nevertheless, Gilbert Kimpton & Company remained one of Leeds’ largest customers.

Leeds’ foreign entanglements were not over, however. In May 1906, the company advertised that a new, premium-priced classical and operatic line of Imperial records was “nearly ready for the trade.”41 A preliminary catalog reportedly was issued the following month. Although Leeds boasted that the records had been made “for us,” they were in fact reissues of material that had already been released in Europe by Schallplatten Fabrik “Favorite” GmbH (Hannover, Germany) on its Favorite label. The more expensive red-label Imperial Grand Opera Records, retailing for $1.50, featured eminent singers from some of the best European houses, but most were unfamiliar to American buyers, and sales appear to have been negligible.42 A $1 black-label series was a hodge-podge of imported band pieces, light classics, and ethnic material. The records went on sale in England in 1907, a futile effort since the same recordings were already available there, on the original Favorite label, for less money. Although a financial failure in both countries, these were Leeds & Catlin’s only legally produced recordings. In 1907, Judge Lacombe ruled that Leeds’ “making of duplicate copies of fully finished commercial foreign records” was not an infringement.43

The British and Grand Opera debacles aside, Leeds & Catlin was rapidly gaining market share, and in early 1906 the Victor Talking Machine Company joined the legal assault. In April of that year, Judge Hazel (United States Circuit Court of Appeals) sustained that part of Victor’s Berliner patent relating to the free-moving stylus for disc records. Victor’s request for a temporary restraining order was granted but then vacated after Leeds attorney Louis Hicks argued that the hurried preparation of what he claimed to be new evidence invalidating the Berliner patent44 would impose an undue hardship.

Leeds’ new evidence, offered up as proof that Berliner’s patent was invalid because it had been anticipated by the work of Bell and Tainter in the United States and Werner Suess in Canada, was presented in due course, this time prompting the Victor attorneys to request an additional delay. An exasperated TMW reporter wrote that “parties undoubtedly close to the facts unhesitatingly predict the entire patent situation will be cleared up inside of six months. How? Ask us something easy.”45

On April 26, Judge Townsend (United States Circuit Court of Appeals) upheld the validity of the Berliner patent and granted a preliminary injunction, which was stayed pending final hearing.46 At the same time, Hicks attempted to distance Leeds & Catlin from co-defendant Talk-O-Phone, falsely asserting that Leeds’ only connection to Talk-O-Phone had been as a customer for its phonographs.47

As the Victor case churned its way through the courts, members of the Leeds family seem to have remained on reasonably friendly terms with executives of other record companies. In May 1906 Loring Leeds became an active member of the newly formed Talking Machine Traveling Men’s Association, where he rubbed shoulders with representatives of Columbia, Hawthorne & Sheble, Zon-O-Phone, and other major producers, with Victor the only notable absence.48 In December of the same year, Edward Leeds joined the Musical Copyright League, an organization that lobbied to have phonograph records exempted from the proposed new copyright law.49

The Victor case was taken up again in the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, on October 11, 1906. The following day, Judge Wallace affirmed the decision in favor of Victor and granted a preliminary injunction. Victor immediately released a statement informing the trade, “We expect to at once proceed to enforce our rights by preliminary injunction against all infringers, including all manufacturers of infringing machines and records who have not taken a license from us, and dealers in such infringing goods.”50

Leeds’ response was to ignore the injunction, leading Victor to file for contempt.51 At the same time, the company advertised that it would market an automatic-feed phonograph.52 The announcement marked a turning point in Leeds’ strategic efforts to evade the Berliner patent. An automatic feed, in theory at least, would skirt Berliner’s specification that the record’s grooves propel the stylus. Reflecting that shift, the company began affixing labels to the reverse sides of their discs stating that the records were sold for use only on automatic-feed machines, or as replacements for worn-out or broken records.

On January 5, 1907, Judge Lacombe (Circuit Court of the United States, Southern District of New York) fined Leeds $1,000 for disobedience of the injunction order. Lacombe noted the sudden appearance of the automatic-feed labels, stating,

No effort to restrict the use to which defendant’s discs should be put by notice on their face or otherwise was made until after motion, and the affidavits are not as satisfying as they might be that such notice has since been affixed; and such notice might fairly go further and advise the purchasers that to use it on one of complainant’s machine would make the user an infringer… Nor is the substitution of these new records…for worn-out discs in any legitimate sense ‘repairs.’”53

Leeds was granted a stay and the fine was suspended, pending yet another appeal. The companies continued to snipe at one another in the trade papers during the interim. Edward F. Leeds declared,

This stay clears the way for the suit which will determine whether or not the record is or is not an integral part of a talking machine and as to the validity of the existing patents. We are now in a position to continue the manufacture of records, and will continue to put out our monthly lists as heretofore, as the stay is indefinite and will continue in force until the decision of the suit, and of that we can foresee but one ending, and that in our favor.54

Victor countered with full-page advertisements, declaring:

1. That the Victor Company controls the disc reproducing machine, comprising the reproducer and the disc record, where the reproducer is vibrated and propelled by the record.

2. That the Victor Company controls this method of reproducing sound.

3. That the Victor Company controls the disc machines for reproducing sound from such records by this method.

4. That the Victor Company controls the disc records for use on these machines.

The Victor Company hesitates at anything like bragging, but some of the advertisements of its competitors make it necessary, in justice to itself, and the trade, to make this statement, so that the fact may be fully appreciated that the Victor Company is on top.55

Leeds finally made its long-delayed re-entry into the cylinder market in January 1907, with its Radium cylinders.56 Despite earlier announcements that the company had already produced 200 masters, only fifteen recordings appeared in the initial list, comprising ordinary popular fare by the usual studio free-lancers. Gaps in the catalog numbers (which ran from 101 through 128) suggest production problems. No further releases are known to have been advertised, and the venture appears to have ended quickly. The only other known mention of Radium cylinders is a June 1907 British announcement that Leeds had promised standard and “extra-length” cylinders to Gilbert & Kimpton in London. However, nothing further was heard of the idea.57

In the meantime, the American Graphophone Company (Columbia) was preparing to rejoin the legal assault on Leeds & Catlin. On February 15, 1907, Columbia attorney C. L. A. Massie requested that Leeds be enjoined from infringing Columbia’s Jones patent, which covered lateral recording in wax.58 On March 25, Judge Lacombe refused to grant an injunction, declaring, “Irrespective of any other point presented on this motion, there is too much dispute as to the process by which defendants’ discs were produced to warrant the granting of a preliminary injunction on affidavits.”59 Request for injunction was again denied on June 11, without leave to renew, and the suit was ordered to go to hearing on its merits.60

In preparation for the hearings, Leeds attorney Louis Hicks wrote to Alexander Graham Bell, requesting a copy of the lecture Bell had delivered to the Fortnightly Club in May 1888. In that talk, Bell had outlined a method of electroplating sound recordings made on “wax or wax-like” discs. Hicks hoped to further bolster his contention that the Jones patent was anticipated by earlier work, and thus was invalid, by obtaining the corroborating testimony of a universally respected scientist. His appeal for Bell’s support was blatantly obvious:

It seems to me just that those who so fully developed the art of duplicating sound recordings at very early dates should make known the facts and not permit others to claim as their own and patent that which was fully invented and disclosed by you and your co-inventors so many years ago.61

Graham supplied Hicks a copy of his Volta Laboratory Description of October 20, 1881, containing the particulars of the process, but no evidence has been found that he granted Hicks’ request for a meeting or otherwise offered him any support.62

In late April, the Victor case reached the United States Circuit Court of Appeals. Having been unsuccessful in attempting to invalidate the Berliner patent, attorney Hicks instead focused on Leeds’ right to sell records for use on non-infringing mecahnical-feed machines, or as replacements for damaged discs under the “repair doctrine.” On May 2, 1907, Judges Coxe and Hough, with Judge Wallace dissenting,63 sustained the lower court’s decision in favor of Victor. The mechanical-feed machine was dismissed as “either as a curiosity or a pretense.” Concerning right of repair, the judges wrote,

The right of general repairing has not been questioned; but what plaintiff in error has done is not to mend or better broken or other records, nor even to furnish new records identical with those originally offered by the Victor Co., but to place upon new discs such other sound records as are thought to command a market, and to induce users of the patented machine not to replace, but to increase their stock of recorded words and music.

The right of repair is measured by the right of the owner of the patented article, and such owner when doing what is above outlined [purchasing unlicensed records] is no more repairing his machine than is one repairing a stereopticon by changing the pictures therein to suit the whim of the person gazing through it.64

A final appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was already in preparation. Papers had been filed on April 6, 1907, and attorneys Hicks and Pettit made a preliminary appearance before the Court on April 14. Edward Leeds seemed particularly buoyed by Judge Wallace’s dissenting opinion.65 On May 28, the Supreme Court agreed to review the validity of the Berliner patent as well as the contempt order handed down by Judge Lacombe.66 Arguments were originally scheduled for the Fall 1908 term, and the outcome was considered to be far from assured. In early 1908, TMW reported that German and other foreign manufacturers were “prepared to spring in” to the American market if the Supreme Court refused to sustain Berliner’s patent.67

In the meantime, production continued as usual. Loring Leeds reported “demand coming from all parts of the globe — South Africa, Russia, India, China, Japan, Philippine Islands, Mexico, South and Central America, England, France, every state in the union.”68 During the summer of 1907 the company took the first orders for its new mechanical-feed phonographs and hired Charles E. Brown as Western sales manager69 and Frederic D. Wood (formerly of the American Record Company) as full-time house conductor.70 In March 1908, Loring Leeds reported an order for 250,000 records from an unspecified Chicago company, most likely O’Neill-James.71

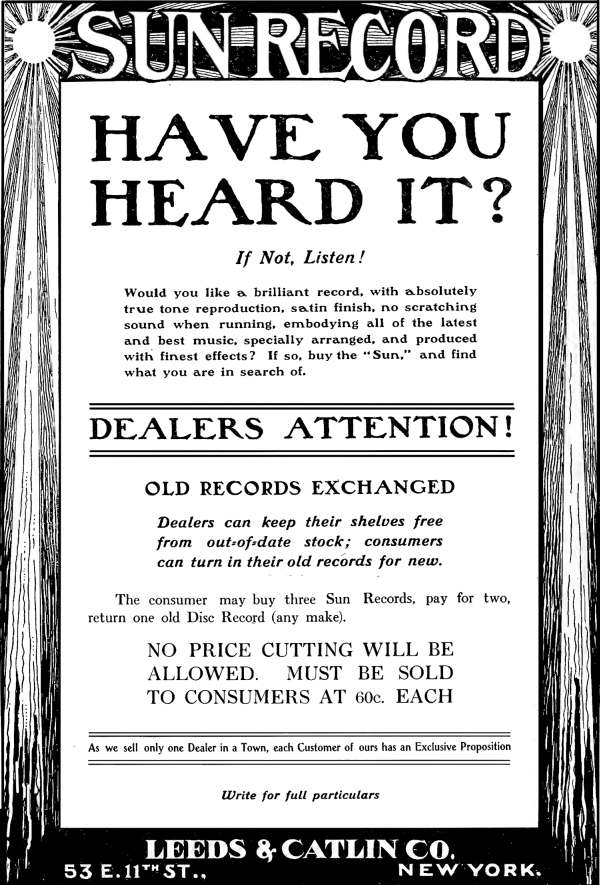

Advertisements began to appear for Leeds & Catlin’s new Sun label in September 1907.72 In October it was reported that Sun would replace Imperial as Leeds’ flagship brand. The first known Sun catalog, published in the same month, included numerous reissues from Imperial and continued that label’s catalog-numbering series. Reports hinted that Imperial would be discontinued, as no new releases had been advertised for several months. However, Leeds did continue to produce new Imperial releases of selected numbers for export. Imperial records from that point forward appeared regularly in the British trade-journal advance lists, but not in their American counterparts. Large quantities of Imperial discs continued to be shipped to England, where surplus inventory was still being sold off as late as 1910.

Final arguments in the Columbia lawsuit, charging infringement of the Jones patent, were heard on June 1–3, 1908 by Judge Hough (United States Circuit Court, Southern District of New York).73 After a considerable delay, Judge Hough handed Leeds & Catlin a rare victory on August 24, invalidating the Jones patent as having been anticipated by Charles Adams-Randall’s 1889 British patents. Predictably, Columbia announced it would appeal.74

President Edward F. Leeds did not live to hear the initial outcome of the Columbia case. He died following a short illness at his summer home near North Long Branch, New Jersey, on August 12, 1908, at the age of forty-three.75 Leeds had labored nearly to the end to skirt Berliner’s patent; eight months before his death, he and George Rumpf filed a patent application on a phonograph with a stationary reproducer mounted above a laterally tracking turntable.76 His position was filled by Frank P. Byrne, a Detroit banker. Increasingly, the company was slipping from the family’s control, with Loring Leeds now the sole family member remaining on the board of directors.

The anticipated autumn 1908 Supreme Court hearing continued to be delayed. While it waited, Victor filed a new lawsuit against Leeds & Catlin, this time charging the company with infringing its patented process for attaching paper labels to discs.77 Finally, on January 14, 1909, Pettit and Hicks were allowed to argue their cases before the Supreme Court justices.78 The court adjourned for mid-winter recess on January 26 without having announced a decision.79 TMW reported,

Much to the disappointment of everybody the Supreme Court of the United States failed to hand down a decision in the case … Downtown in New York it was the universal topic of conversation, and even business was neglected at times to discuss the probability of the court’s action with every newcomer…Wagers have been freely made as to the outcome.80

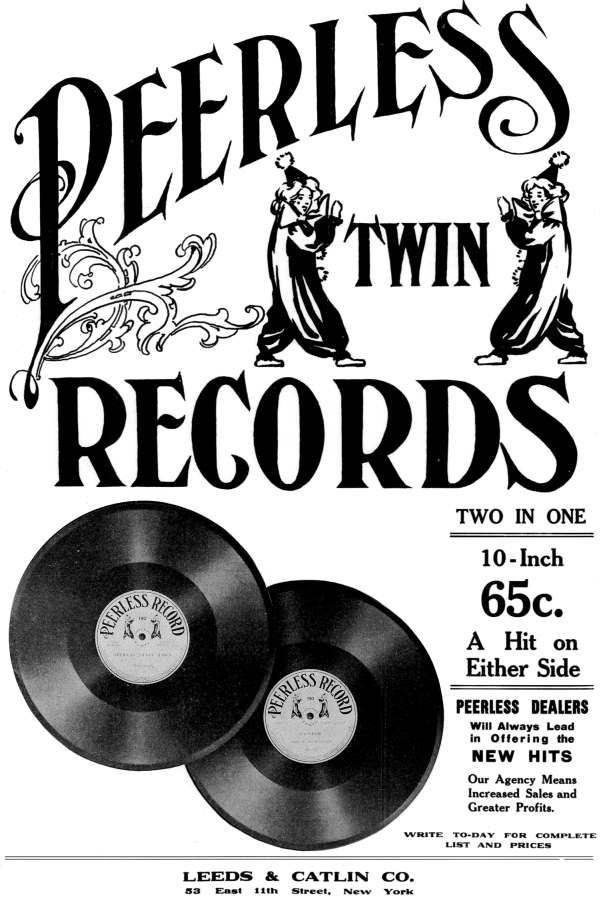

During the summer of 1908, Walter L. Eckhardt had been installed as Leeds’ new general manager and a member of the board of directors. Among other duties, he was soon assigned to develop and market Leeds’ new double-sided Peerless discs.81 Eckhardt’s arrival coincided with the disappearance from TMW of advertisements for Leeds’ single-sided Sun records, suggesting that the company was already planning its transition to double-sided pressings. The records were to retail for 65¢, the same as Columbia’s Double Discs, and a dime less than Victor’s new double-sided line. The name quite likely was suggested by Eckhardt, whose Manufacturers’ Outlet Company was already marketing a line of household appliances under the Peerless brand. Peerless phonographs, marketed by Manufacturers’ Outlet, were first mentioned in TMW in September 1908, the same month in which Columbia, Victor, and Zonophone announced their forthcoming double-sided lines.82 The records themselves are not known to have been advertised until February 1909, when Leeds took a full-page Peerless ad in TMW83 and published their March advance list.84 By that time, however, the catalog numbering (which began at #101) had already reached #189, offering evidence that the records had already been on the market for several months by that time.

Eckhardt’s arrival seems to have signaled a shift in Leeds’ corporate structure and marketing arrangements. In February 1909, his Manufacturers’ Outlet Company (89 Chambers Street, New York) took over distribution of the entire Leeds & Catlin line,85 and arrangements were made to move into larger offices. TMW reported that Eckhardt had booked a 100,000-disc order for an undisclosed Chicago company, most likely D&R.86 During one well-reported party at New York’s Knickerbocker Hotel, Eckhardt offered a recording contract to baritone Antonio Scotti (one of Victor’s most prestigious Red Seal artists), which Scotti politely declined.87

Despite Eckhardt’s best efforts, the protracted litigation was taking a toll. In March 1909, the company ran its last list of Peerless records in TMW, as April releases. The 1908 ruling favoring Leeds in the Columbia case had been reversed on appeal, and on April 14, 1909, the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, New York City, unanimously upheld the validity of Columbia’s Jones patent for a second time.88 In rejecting Leeds’ argument that the Jones patent was anticipated by the Adams-Randall patent, the judges wrote,

If today a skilled artisan, who had never heard of the Jones or Adams-Randall patents, were given a Jones disc and the Adams-Randall patent, and directed, after reading the patent, to construct similar discs, we doubt whether he would be able to do so.

Is not the fact that the patent was never heard of, until it was resurrected for the purpose of this litigation, persuasive evidence that it contained nothing of value to the art? … We are unable to see that Adams-Randall’s contribution to the art advanced it a single step.

Three days later, Judge Lacombe granted a decree for a perpetual injunction, an accounting of Leeds & Catlin’s profits accruing under their infringement, and an accounting of damages the American Graphophone and Columbia Phonograph companies had sustained as a result of the infringement. Louis Hicks’ appeal to the Supreme Court on Leeds & Catlin’s behalf was peremptorily denied.89

Finally, on April 19, 1909, the Supreme Court announced its decision in the Victor case, upholding Leeds’ $1000 fine in the 1907 contempt case, striking down the company’s claim to right of repair and replacement, and withholding judgment on the mechanical-feed issue.90 But most importantly, it decisively upheld the validity of Victor’s Berliner patent.91 A preliminary injunction was granted, effectively signalling the end for Leeds & Catlin. In a lengthy statement to the trade, Victor president Eldridge Johnson declared,

Around every successful enterprise stand, in a crowded circle like wolves surrounding a herd of buffalo on the plains, certain envious ones who hope, by some lucky circumstance, to share in the reward due to others. The talking machine business seems to be more than ordinarily attractive meat, and I know of many seemingly bright and able men who have left the bounteous open field of a business, theirs by opportunity and training, to try to break into the talking machine business. It is the same sad old tale of forbidden fruit. Some other fellow’s business is always the best.

To imitate goods that others have developed at a great cost, for the purpose of saving a certain percentage of overhead expense by dispensing with a department of engineering, development and design, appeals strongly to men who do not understand the talking machine business and its future…. Practically every concern that has tried to jump into our trade in this manner has gone to the wall before litigation which we were able to bring against them could come to final hearing, and this is one reason why the Victor Co. has been so long in sustaining its patents. Many pathetic stories have been recited to us by innocent investors, who were told that the talking machine business was a rare field of profit. Of course these victims always come to us as a last resort and try to sell us their enterprise, which we have invariably found to be useless…92

Armed with such a decisive ruling, Victor went on to successfully sue other infringing manufacturers, including Duplex and Sonora. Nor were dealers in infringing merchandise safe from Victor’s attorneys. On May 29, 1909, the company filed suit against R. H. Macy & Company for selling Leeds-produced Nassau records, submitting “a formidable document two inches thick,” according to TMW.93 A restraining order was granted immediately, sending a clear and highly publicized warning to others in the trade. On June 19, Judge Lacombe wrote, “What defendants may do with the infringing discs they now own is a question to be dealt with when it arises.” He went on to opine that infringement would be unlikely if the records were shipped abroad, provided they were sold only after their arrival offshore.94

The Supreme Court decision and Macy’s case had an immediate chilling effect on the sale of Leeds’ remaining inventory. As a result of the Supreme Court ruling, one attorney noted, “Numerous records had been previously sold and the purchasers would not pay for them now for fear of being involved in litigation. The stock on hand was largely of the same kind, and is practically valueless, as it cannot be disposed of."96

On June 21, 1909, the Leeds & Catlin Company was petitioned into bankruptcy by attorney Leonard Bronner, on behalf of several creditors.95 Theodore Taft was appointed as receiver the following day.97 Among the creditors was the O’Neill-James Company, the marketer of Busy Bee discs, which filed a claim for $35,000.98

On August 10, 1909, most of Leeds & Catlin’s property at its New York office and studio was sold at public auction. Among the items listed for sale were Talk-O-Phone, Leeds, Imperial, Sun, Nassau, Concert, Symphony, and Sir Henri discs; cylinder and disc masters; one disc and four cylinder recording machines; and, ironically, a Victor phonograph.99 The sale realized $2,400, less than 75% of appraised value, which was estimated at something over $3,500. However, the articles sold represented only a small portion of the company’s assets. Still to be sold were the factory and equipment at Middletown, Connecticut, along with unspecified patents reportedly valued at $1.5 million. “The patents,” TMW noted, “have caused some inquiry as to their nature, as they are comparatively unknown in the trade.”100

The contents of the Middletown plant were eventually sold at auction on February 10, 1910,101 but not before a Victor representative addressed the crowd, as TMW reported:

An attorney of the Victor Talking Machine Co. stood beside the auctioneer, and with great deliberation and much emphasis read the decision rendered by the Supreme Court of the United States in the Berliner patent case, an opinion which adjudicated the validity of that famous invention for all time. This was in the nature of a warning to prospective buyers; but somehow this peculiar incident seemed in keeping with the close of the turbulent and militant career of the bankrupt manufacturers.102

Receivership terminated on February 28, 1910, with bond holders receiving only a small percentage of face value.103 However, issues surrounding the bankruptcy continued to surface. Columbia obtained a final ruling on damages in April 1910, under which Leeds & Catlin was held accountable for $81,250.85 in damages for infringement of the Jones patent.104 As part of an earlier settlement with the Talk-O-Phone Company, Columbia had received a quantity of Talk-O-Phone cabinets, which it outfitted with its own works for several client machines in 1910. Columbia also allowed jobbers to exchange their now-unsalable Leeds & Catlin pressings for Columbia records. In an unfortunate miscalculation, Columbia then sold the discs to the Simpson-Crawford Company, relabeled as Sir Henri records, leading Victor to sue Columbia for the sale of infringing products.105 Victor initially won its case in U.S. Circuit Court,106 but the decision was later reversed on appeal,107 with the judge writing,

Leeds & Catlin sold a large quantity of these records to various jobbers, which the Graphophone Company took off the hands of the jobbers in exchange for their own records, made under the Jones patent. Some of these records it subsequently sold, and it was for this the Circuit Court held it to be a contributory infringer. … We cannot see that the Victor Company’s business is any more or any differently injured by the Graphophone Company’s selling Leeds & Catlin records than it is by that company’s selling its own records. On this point it is suggested that the Leeds & Catlin record is an inferior one. If so, not being sold as the Victor Company’s, the business of that company is less likely to be injured by the sale than is the Graphophone Company’s business.108

Columbia was not the only company to be saddled with unsalable infringing discs following Leeds & Catlin’s demise. A flourishing black market developed as jobbers and retailers attempted to unload their devalued inventories of Leeds merchandise. Victor was especially vigilant in ferreting them out, at one point even employing private detectives to follow individuals suspected of dealing in the infringing records.109

Victor brought a final suit against what remained of the Leeds & Catlin Company in June 1910, seeking a ruling from the U.S. Circuit Court that they could use in possible future cases of patent infringement.110 Judge Hand declined to rule. For a short time it was rumored that Leeds might resume record production, but the forced sale of its Middletown real estate in October 1912 put an end to the speculation. The company’s remaining equipment and furnishings were not disposed of until September 23, 1914, when they were auctioned to recover the cost of storage.111

Loring Leeds went on to work as manager of the Boston Talking Machine Company, the ill-fated manufacturer of Phono-Cut records. He played a key role in designing the company’s plant but resigned his position for unexplained reasons on September 9, 1913, stating that he had “no future plans” other than to relax at his New Jersey home.112 He resurfaced several months later as sales manager of Pathé’s New York office. In 1917 he attempted to revive the Leeds brand, launching the Leeds Phonograph Record Company in New York.113 The incorporation notice stated that the company was to “manufacture and deal in phonograph records” and other merchandise, but no records are known to have been produced.

Notes

1 “Trade Notes.” The Phonoscope (November 1896), p. 9.

2 “Records 50 Cts. Each” (advertisement). The Phonoscope (November 1896), p. 4.

3 National Phonograph Company ledgers, reported in: Wile, Raymond. “Duplicates in the Nineties and the National Phonograph Company’s Bloc Numbered System.” ARCS Journal (Fall 2001), pp. 188–189. A list of confirmed Walcutt & Leeds masters used by Edison can be found in Edison Two-Minute and Concert Cylinders: American Issues, 1897–1912 (Allan Sutton, Mainspring Press, 2015).

4 “Legal Notices.” The Phonoscope (March 1898), p. 9.

5 American Graphophone Co. v. Waluctt and Leeds. U.S. Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York. In equity 6542.

6 Excelsior & Musical Phonograph Co. … Selling Agents for the Celebrated Walcutt & Leeds Records” (advertisement). The Phonoscope (June 1899), p. 4.

7 “New Corporations.” The Phonoscope (April 1899), p. 15. The Phonoscope’s cover dates at this time bore no resemblance to actual publication dates.

8 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (September 15, 1908), p. 44.

The recordings were made by Leeds for the Bigelow & Main Company. J. Allen Sankey later served on Leeds & Catlin’s board of directors.

9 Quoted in “Current Collectors’ Recordings: The Recordings of Moody and Sankey.” Hobbies (May 1956), p. 33.

10 “To Manufacture in Toledo.” Music Trade Review (January 11, 1902) , p. 39.

11 No details of Bradley’s alleged early pirating activities have been uncovered, but in a later well-documented lawsuit, Bradley was found to be the driving force behind the Continental Record Company, which pirated Victor and Fonotipia recordings.

12 Bradley, Winant Van Zant P.: “Talk-O-Phone.” U.S. Patent and Trademark Office: Label Registration #38,668 (application filed May 10, 1902, with use on phonographs claimed since January 1, 1902).

13 Although Bradley’s Monogram trademark application, filed on May 5, 1902, claimed use on disc records since January 2, 1902, the earliest known Monogram advertising appears in a 1903 Talk-O-Phone catalog. Ohio Talking Machine claimed to operate a recording studio in Toledo, and in view of the obscure artists who appear on Monogram records, that was quite likely the case.

14 On October 28, 1903, it was announced the Ohio Talking Machine Company would soon cease to exist, and that its place would be taken by a new corporation, to be called the Talk-O-Phone Company. The exact date of the transition has not been discovered; however, Ohio Talking Machine was still operational as late as November 3, 1903, when it filed a trademark application for its parrot-and-phonograph logo (U.S. trademark filing #41,584).

15 “The Talk-O-Phone. Leeds Records” (advertisement). New York Times (December 6, 1903), p. 22.

16 “In the Talking Machine World.” Music Trade Review (December 17, 1904), p. 45.

18 “Court Calendars.” New York Times (May 14, 1904).

19 American Graphophone Co. v. Leeds & Catlin Co. et al. Circuit Court, S.D. New York. July 9, 1904. 131 F. 281.

20 American Graphophone Co. v. Leeds & Catlin Co. et al. Circuit Court, S.D. New York. August 14, 1905. 140 F. 981.

21 “Leeds & Catlin’s Handsome New Plant at Middletown, Connecticut.” Music Trade Review (September 2, 1905), p. 43.

22 “Leeds & Catlin’s New Plant.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1905), p. 38. There is no record of Edward Leeds having filed for a U.S. patent prior to March 1906.

23 Imperial discs were first advertised in June 1905. Concert’s launch date has never been determined, although it is believed to have preceded Imperial’s introduction.

24 “The Imperial Record…Is Now Retailed at Sixty Cents” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (December 15, 1905), p. 38.

25 “Talking Machines Cut” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (February 15, 1906),

p. 30. The same ad offered heavily discounted front-mount Talk-O-Phone machines, which had recently been supplanted by new tapered–tone arm models.

26 “Important to Leeds & Catlin Dealers” (advertisement). Music Trade Review (January 19, 1907), p. 47.

27 Gilliland, W. Ezra. Letter to Frank L. Dyer (March 30, 1905). Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, NJ.

28 Baucus, Joseph D. Letter to Frank L. Dyer, re: New York Phonograph Company and Catlin and Leeds [sic] (April 6, 1905). Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, NJ.

29 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1906), p. 6

30 “Inquiry About Hard Records.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1906), p. 11.

31 “Who Can Answer These Queries?” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1906), p. 6.

32 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (March 15, 1906), p. 11.

33 “Trade News from All Points of the Compass.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1906),

p. 28.

34 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (February 15, 1906), p. 26. The same notice reported that Leeds & Catlin had opened a coin-slot machine operation.

35 Andrews, Frank. “Imperial Records: Their History in Britain and the Circumstances Surrounding Their Production in the United States of America,” p. 2. Unpublished manuscript (William R. Bryant papers, Mainspring Press).

37 “Tom Child Will Sing for Leeds & Catlin Co.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1907), p. 21.

38 “Ian Colquhoun in New York.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1907), p. 39.

39 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1908), p. 28.

40 “To Form Big English Company.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1907), p. 34.

41 “The Records Made for Us in Europe…” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (May 15, 1906), p. 10.

42 “The New Imperial Records Recorded in Europe” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (June 15, 1906), p. 44.

43 American Graphophone Co. v. Leeds & Catlin (155 F. 427).

44 Leeds’ defense hinged on the claim that Berliner’s patent was invalid because it had been anticipated by the work of Bell and Tainter in the United States and Werner Suess in Canada.

45 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1906), p. 32.

46 Victor Talking Machine Co. et al. v. Leeds & Catlin Co. Circuit Court, S.D. New York. April 26, 1906. 146 F. 534.

47 “Not Directly Concerned.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1906), p. 23.

48 “Traveling Men Organize.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1906), p. 25.

49 “Musical Copyright League.” Talking Machine World (November 15, 1906), p. 43. Harry F. Leeds, Jr., took his place a year later.

50 “Victor Co. Announcement.” Talking Machine World (November 15, 1906), p. 58.

51 “Some ‘Talker’ Litigations.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1906), p. 42.

52 “Our Mail Bag” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (November 15, 1906), p. 2. These are likely to have been manufactured by Talk-O-Phone or another outside supplier; no evidence has been found that Leeds operated its own phonograph factory.

53 “Victor vs. Leeds & Catlin Suit.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1907), p. 33.

54 “Leeds & Catlin Secure Stay.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1907), p. 33.

55 “What the Victor Company’s Victories Mean” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (March 15, 1907), p. 5

56 “Important to Leeds & Catlin Co. Dealers,” op. cit. Loring Leeds reportedly was showing samples of the cylinders to dealers as early as December 1906. Although examples of Radium boxes have been reported, the authors are not aware of any surviving specimens of the cylinders themselves.

57 Andrews, Frank, op. cit., p. 4.

58 “Apply for Injunction.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1907), p. 48.

59 “Preliminary Injunction Refused.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1907), p. 52.

60 “Recent Legal Decisions.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1907), p. 40.

61 Hicks, Louis. Letter to Alexander Graham Bell (August 28, 1907). The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

62 Hicks, Louis. Letter to Alexander Graham Bell (September 13, 1907). The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

63 Wallace retired several days after writing his dissenting opinion.

64 “The Victor Co. Suit.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1907), p. 47.

66 “To Review Litigation.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1907), p. 62.

67 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1908), p. 39.

68 “Brieflets.” Talking Machine World (July 15, 1907), p. 49.

69 Brown was originally hired as general sales manager, the position held by Loring Leeds. However, he retained his stake in two San Francisco businesses, including a Talk-O-Phone dealership, and plans to move him (at first to New York, then to Chicago) were quickly scuttled. In the end, Loring Leeds remained in place as general manager for Eastern and international sales, leaving Brown to cover only the Western states. He left the company after several months.

70 “Here and There in the Trade.” Talking Machine World (August 15, 1907), p. 59. It is not known who conducted the house ensembles prior to Wood’s arrival.

71 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (April 15, 1908), p. 7. O’Neill-James marketed Busy Bee and (through an O’Neill subsidiary) Aretino discs.

72 “Sun Record Outshines Them All!” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (September 15, 1907), p. 41.

73 “Final Arguments Heard.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1908), p. 38.

74 “Important Decision in Jones Patent Suit.” Talking Machine World (September 15, 1908), p. 36. The decision was quickly reveresed on appeal

75 “Death of Edward F. Leeds.” Talking Machine World (August 1908), p.

76 Leeds, Edward F. and Rumpf, George. “Phonograph.” U.S Patent #897,836 (filed January 18, 1908; granted September 1, 1908). Hawthorne & Sheble manufactured the machine for Aretino in 1908.

77 “Victor vs. Leeds & Catlin Suit.” Talking Machine World (November 15, 1908), p. 42.

78 “Victor–Leeds & Catlin Case Up.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1909), p. 58.

79 “No Decision in Important Cases” Talking Machine World (February 15, 1909), p. 78. Several weeks later, Hicks accepted a position on the legal staff of the National Phonograph Company (Edison).

80 “No Decision Yet.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1909), p. 55.

81 “Eckhardt Is General Manager.” Talking Machine World (February 15, 1909), p. 38.

82 “A Word With You, Mr. Talking Machine Dealer.” Talking Machine World (September 15, 1909), p. 38.

83 “Peerless Twin Records” (advertisement). Talking Machine World (February 15, 1909), p. 50.

84 “Peerless Twin Records—March List.” Talking Machine World (February 15, 1909), p. 55.

85 “Sales Agent for Leeds & Catlin.” Talking Machine World (February 15, 1909), p. 72.

86 The D&R Record Company, Leeds’ last major client, was incorporated in Chicago in January 1908. Its first catalog of Double & Reversible Records consisted entirely of Leeds pressings.

87 “Scotti Declined.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1909), p. 54.

88 “Jones Patent Again Decalred Valid.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1909), p. 36.

89 “Motion for Writ Denied.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1909), p. 6.

90 “Decision in Contempt Suit.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1909), p. 6.

91 “Berliner Patent Finally Adjudicated.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1909), p. 25–26.

92 Johnson, Eldridge R. “The Recent United States Supreme Court Decision; Its Effect; and the Future of the Talking Machine Business.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1909), p. 12.

93 “Brings Suit Against Macy & Co.” Talking Machine World (June 15, 1909), p. 27. Macy’s reportedly had 20,000 Nassau discs in stock at the time

94 “Suit for Patent Infringement.” Talking Machine World (July 15, 1909), p. 58.

95 “Leeds & Catlin Co. Fails.” New York Times (June 22, 1909), p. 55.

96 “Leeds & Catlin in Trouble.” Talking Machine World (July 15, 1909), p. 55.

97 “Business Troubles.” New York Times (June 23, 1909), p. 14.

98 “Business Troubles.” New York Times (July 31, 1909), p.12.

99 “Bankruptcy Sales.” New York Times (August 10, 1909), p. 13.

100 “Leeds & Catlin Sale.” Talking Machine World (August 15, 1909), p. 27.

101 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (February 15, 1910), p. 27.

102 “Timely Talks on Timely Topics.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1908), p. 28.

103 “Assets to Be Distributed.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1908), p. 34.

104 “Referee Award $81,250.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1910), p. 33.

105 “Court Holds with Victor Co.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1910), p. 40.

106 Victor Talking Machine Co. v. American Graphophone Co. Circuit Court, S.D. New York (April 6, 1910). 178 F. 577.

107 “American Graphophone Co. Win Suit.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1910), p. 33.

108 American Graphophone Co. v. Victor Talking Machine Co. Circuit Court, D. New Jersey (January 3, 1911). 183 F. 580.

109 See for example, Victor Talking Machine Co. et al. v. Greenburg. Circuit Court, S.D. New York (May 24, 1910). 181 F.543.

110 Victor Talking Machine Co. et al. v. Leeds & Catlin Co. Circuit Court, S.D. New York (June 1, 1910). 180 F. 778.

111 “Bankruptcy Sales.” New York Times (September 23, 1914), p. 14.

112 “L. L. Leeds Resigns as Manager.” Talking Machine World (September 15, 1913), p. 19.

113 “Latest Business Brieflets for the Busy Reader.” Music Trade Review (February 17, 1917), p. 26.